By MARCIA R. LIEBERMAN – February 11, 2001 – New York Times

Philip Lieberman

When I first heard of a Jeep safari in Himalayan India, I was puzzled. I had traveled in the Himalayas and knew that it was rare to be able to get anywhere in those mountains other than on foot. But the region of Spiti, in Himachal Pradesh, in India’s north, is an exception: it offers Jeep travel as well as trekking possibilities.

I knew little about Spiti except that it was the site of one of the greatest surviving monuments of Tibetan art, the Tabo monastery. We learned more in the summer of 1999, while trekking through Ladakh and Zanskar, just to the west, with a guide from Spiti. Together, these regions were once part of western Tibet and remain ethnically Tibetan. Intrigued, we planned a trip for August, 2000.

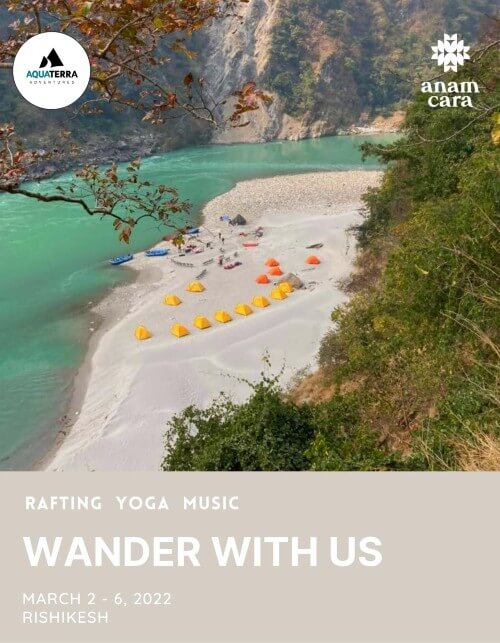

We arranged our three-week tour through Aquaterra Adventures, an Indian agency specializing in Himalayan travel. Our safari consisted of two Jeeps. My husband, Phil, and I, along with our guide, rode in one. Sukman, our cook, and his helper followed in the second with the food, fuel and general camp gear.

Two careful Indian drivers negotiated the trans-Himalayan roads, occasionally fording rivers and ascending steep, rocky tracks signposted as “jeepable.” That there were roads through this rugged terrain, even roads that were only jeepable, was astonishing enough. “This place is no place for men,” Rudyard Kipling wrote of Spiti in his novel “Kim.”

Yet the presence of these roads allowed us not only to drive along the Spiti Valley but also to explore side valleys on the way. Typical daily excursions varied from 20 to 60 miles.

We camped sometimes in spectacular, vast, empty spaces next to mountain lakes, at other times beside farms. We took our own sleeping bags and tent, although Aquaterra can provide all necessary gear. We visited thousand-year-old Buddhist monasteries and traditional villages — places that in other parts of the Himalayas can be seen only by strenuous hiking.

Departing from Manali (having arrived there by car from Delhi), we approached Spiti from the valley of the Chandra River, then drove to the Lake of the Moon — the Chandra Tal. We reached the Chandra Tal in two days, stopping to camp overnight beside the Chandra River.

The Chandra valley, sown with boulders, looks like the bowling alley of savage gods. We turned off the road onto a narrow, stony track. Our driver, with steady nerves, proceeded cautiously as we climbed high above the valley, with precipitous drops to one side. It seemed as if we were heading into the heart of a wasteland when we suddenly caught sight of the lake, its searing turquoise color a visual shock in this barren, stony landscape.

Our crew set up camp above the lake, at 14,000 feet. I found myself a little breathless, but it helped to walk around slowly. With Dorje, our personable young English-speaking guide, we strolled around the milelong lake. The shores were tinged with pale green, dotted with a profusion of tiny edelweiss. Beyond the lake rose distant, sharp-edged mountains capped with snow. In the late afternoon sun the bare, craggy slopes turned pastel shades of sand, peach and mauve. Waterfowl with long dark beaks, white underbellies, and brown backs cruised the water.

Himachal Pradesh is creating a park here, and we came across workers laying out a path. The only other person we saw during our walk of an hour and a half was a shepherd at the far end of the lake, tending a flock grazing on a green meadow. How could a place so verdant, I wondered, suddenly appear in the midst of what seemed a wasteland? But such surprises, we were to discover, characterize this land of abrupt changes.

That night, as he did throughout the trip, Sukman served us a tasty and varied vegetarian meal. His specialties included traditional dal (lentils) with rice, noodles cooked with vegetables, potato dishes, and momo (Tibetan dumplings), along with stir-fried vegetables. Dessert was usually fruit, but once there was an apple tart and once a chocolate cake. For breakfast we had porridge or cold cereal; pancakes and eggs were offered as well. Lunches were usually chapatti (Indian flatbread) sandwiches filled with peanut butter and jam, with a bit of cheese or a packet of cooked potato or mushrooms.

The next morning Dorje led us from our campsite on a trail from which we gazed down on the valley we had traversed the day before by Jeep. Here above, in contrast to the barrenness below, the slopes were green and the Pier Panjaal mountain range spread before us in a splendid panorama.

Crossing over a ridge, we descended three and a half hours later and rejoined the road at the Kunzum Pass, where our two Jeeps met us. Here was a small Buddhist shrine festooned with Tibetan prayer flags, a flurry of brilliant color against a backdrop of snowy mountains. We watched pilgrims stop to pray and touch something on the shrine. Dorje explained that they put a coin on a stone embedded within the shrine; if one’s heart is pure, the coin will stick — otherwise, it will fall.

We camped in Losar, the first village we came to in Spiti. Its few houses are in the Tibetan style, whitewashed cubes with tiny windows outlined with black paint, and a black-and-red stripe painted just below a flat roof piled with brushwood and bristling with prayer flags. A grandmotherly old woman near our camp was making tsampa, the staple food of Tibetan peoples. She scooped up grains of parched barley from a mat, tossed them into a flat pan, and roasted them over a fire. Beckoning to us with a smile, she offered us a taste; the tsampa had a pleasingly nutty flavor.

Dorje’s family came from Spiti, and wherever we stopped, there was always a friend to shake hands with. At Yangchen Choling convent, home to 15 Buddhist nuns who raise medicinal plants, the mother superior asked Dorje for a ride up the road, and we welcomed her into our Jeep. When we stopped at the village of Kiato to visit a small monastery, a man in a nearby house hailed Dorje and asked him to come in. We were invited too, and joined a large, jolly family eating a late-morning meal of dumpling soup. We sat cross-legged on a mat, and were offered cups of Tibetan tea, a brew flavored with salt and yak butter.

The village of Dankhar, formerly the capital of Spiti, is the site of one of its oldest monasteries, in a spectacular site atop a rocky crest overlooking the confluence of the Spiti and Pin Rivers. Below the whitewashed monastery, the little village seems to hang down the slope, its emerald fields of barley in startling contrast to the barren landscape. A steep path led us to the chapels, of which the topmost is balanced on the cusp of the cliff, with a bird’s-eye view of the Spiti valley.

An hour’s hike above the monastery brought us to Dankhar Lake, its deep blue-green color strikingly different from the turquoise Chandra Tal. Behind pinkish-brown hills rose a distant backdrop of snowy peaks. Tiny black salamanders scurried along the shore; we watched a bird neatly spear a fish. At a higher altitude, the color of the sky deepened to pure lapis lazuli. The silence was absolute, and we were alone: a side of India totally unexpected.

Although one attraction that lured us to Spiti was Tabo, its greatest monastery, nothing prepared me for the actuality. Tabo is one of the glories of Tibetan art. I had imagined a single big temple but found instead a large complex with numerous chapels besides the main prayer hall, nine painted rooms in all, with magnificent murals.

Built in 996, Tabo is a rare survivor from the early period of Tibetan Buddhism and contains a treasure of superb early Indo-Tibetan art. It was founded by the 10th- century scholar Rinchen Zangpo, whose translations of Sanskrit texts were of fundamental importance to the establishment of Buddhism in Tibet. Tabo is not merely a monastery, or gompa, but also a chokhor, a scholastic foundation, akin to the great medieval European monastic centers of learning. It now has a community of 50 monks. While we were there, several other groups of tourists arrived, but there were no crowds.

Tabo’s oldest paintings, from the mid-11th century, are in the Tsug Lhakang, the main prayer hall. Buddhist deities, broad-shouldered and narrow-waisted in Indian and Kashmiri style, are shown against a background of scrolling vines and flowers. The paintings also depict great lamas, historical personages and a host of colorful witnesses in various sorts of central Asian dress.

Placed around the walls are painted clay statues, the finest sculptural examples of the period. The arrangement of these paintings and statues forms a unified composition, a mandala that illustrates the path to enlightenment. Other highlights include the 16th-century murals in the Serkhang Chapel and the painted ceiling of the Domton Lhakang Chenpo.

Equally worth visiting is Phu, a small cave gompa across the road, considered part of the original Tabo group. Its paintings also date from the early 11th century.

We found comparably superb paintings and statues at Lhalung Gompa, a thousand-year-old Buddhist monastery nearly 13,000 feet above a tributary of the Spiti River. Here an elderly lama solemnly told us that Lhalung was one of three monasteries built on the same night by Rinchen Zangpo (the other two being Alchi, in Ladakh, and Tabo). The great willow tree in the courtyard, he added, had also been planted by the sage, as a stick. We murmured politely in wonder, but later, as we drove down from the monastery through a landscape of gigantic formations of rock, with walls as big as the north face of the Eiger, dwarfing any human sense of scale, it suddenly seemed that the stories could indeed fit this impossible landscape.

Knowing that we wanted to see traditional village life, Dorje led us to Mane, a village completely off the usual tourist circuit, home to 250 people. We strolled for several hours through fields of peas, wheat and barley, which men and women were harvesting with sickles. Above the upper village, we watched a man threshing with 12 donkeys, singing as he drove them round and round, while another man flattened an earthen threshing floor with a wooden mallet. Around the village houses were kitchen gardens blooming with the pink and white flowers of young potato plants.

In the hamlet of Shego, we camped at a farm beside fields of peas and barley, while attending a great ceremony, a Kalachakra initiation, held by the Dalai Lama at the nearby Kyi monastery. The festival included a day of traditional dances. When the farmer’s wife asked if we could take her to the festival, we happily agreed. In her finest traditional dress, her baby wrapped in a shawl, she climbed into our Jeep. We sat together at the outdoor festival amid a great throng of local people as well as some tourists, through which we could just barely see the Dalai Lama, who sat in a covered pavilion.

That evening the farmer’s wife invited us for tea. We sat in a room with mud floors and a ceiling of twigs and branches, where she served us a plate of sweet, freshly picked peas with Tibetan tea. In this room, traditional in every way, an Indian movie flickered on a television set — the reception blurry and the sound poor, yet a sign of change coming even to this remote mountain land.

Another day we visited a few remote monasteries, and again met a surprise. Above a deep, narrow gorge, we emerged into green, rolling country, a landscape unlike any we had yet seen. Cows and yaks grazed on grass and little green shrubs, and the snow-topped mountains were even closer.

After visiting a small gompa, we sat on the ground to eat lunch. A little girl, her baby brother on her back, toiled up the slope to sell us a few ammonite fossils, abundant in this region. I offered her the chocolate bar our cook had put in my lunch bag. I had never given candy to the children who, across the Himalayas, beg for sweets, but she had not begged. She shook her head. She had never seen chocolate and was afraid to try it.